Masquerade Ball – The Glamourous History & A Gruesome Moment Behind This Costume-Culture Party-Phenomenon

The Masquerade ball theme has been around for centuries. So it comes as no surprise to learn that we might have forgotten the true origins of Masquerade. Its timeline goes back to the 14th and 15th centuries when Europeans were hosting carnivals.

Someone might have said, ‘We doeth the same thing every year. Canst we not shaketh things up a little?’ And some drunk guy or gal might have responded, ‘Why, let’s throweth ourselves a ball, and let us all not knoweth who’s attending it.’

Now that I am done butchering Old English, let’s go on a journey, a journey fraught with unexpected twists and even stranger truths. This is the journey of the Masquerade ball.

For The Sake of All That is Holy, Why Did they Do It At All?

For precisely a holy sake did they do it, my good friend. Historically, Christians celebrated such events before Lent. It was a symbolic festivity to let people know that they needed to eat and drink as much as they can, because ‘Lent’ was all about the opposite, namely fasting.

These dances did away with social restrictions, meaning the rich and poor alike mingled and caroused. ‘Lent’ was considered a time of strict self-sacrifice, meaning any personal ‘desires’ that people harbored needed to be dealt with, and fast. Masked parties seemed an ideal time to indulge in ‘unholy acts’ and be done with them before ‘Lent’. A bit convenient, if you ask us, but we aren’t really complaining.

It’s funny they call this a ‘Christian’ concept because the only real connection that Masquerades have with Christianity is in the Latin words ‘carne vale’ meaning “farewell to meat”. Again, this was a reference to the ‘Lent’ season where everyone refrained from eating meat.

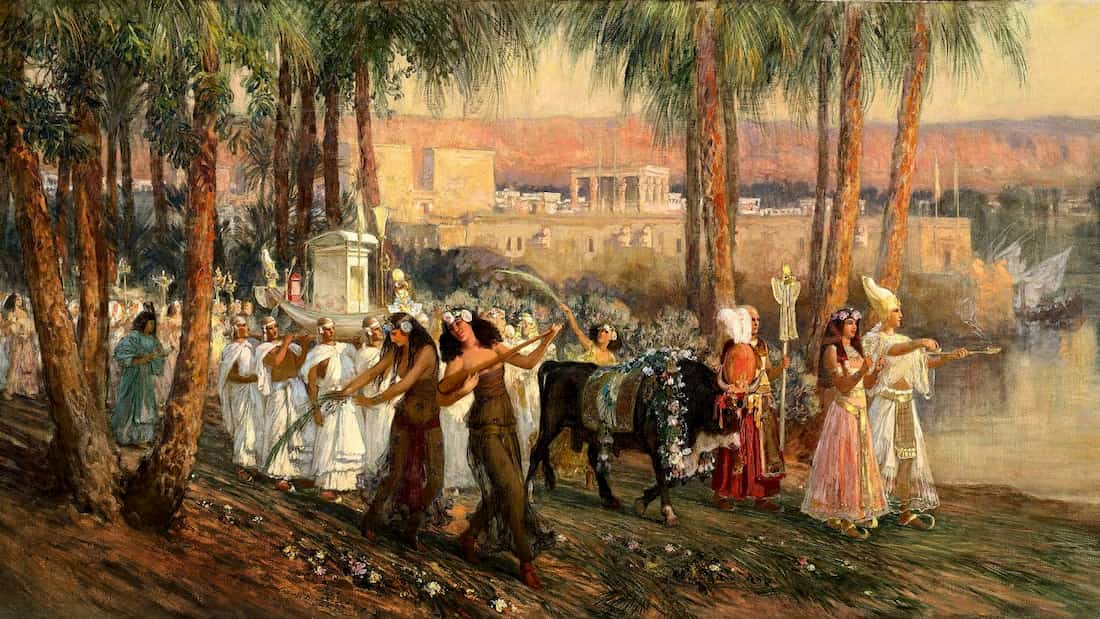

An interesting origin-story for costume use in Masquerades can be found on DiscoveryGrey (the website):

“[T]he idea of dressing up for spring stems from the festival of Isis, Carrus Navalis. Roughly translated as “naval cart”, ancient Egyptians would carry images of the goddess Isis out to sea to bless the first sailors setting off after winter. This march was accompanied by a parade of people dressed like animals and other sacred costumes.”

Who Did Start The Fire?

Masquerade wasn’t always a high-society choice, in fact, it started out as a common celebration. Villagers would don costumes and engage in processions and pageants with glamorous abandon. As with most fashionable things, this idea took off in France.

These masked events were also thrown to honor or welcome visiting royalty. This was when the theme really took flight, particularly thanks to Charles VI of France. In 1393, he decided to copy what the peasants were doing. As a result, the first-ever “Bal des Ardents” (Translation: The Burning Men’s Ball) was held. This event took the previously decadent Masquerade party concept and infused it with an element of nocturnal frolicking, risk, and a generous helping of intrigue.

The party wasn’t really sophisticated or refined, especially when you consider the fact that King Charles and five bizarrely brave courtiers dressed up like ‘wild men of the woods’, wore flax costumes and masks, and performed a rather dangerous dance.

Who’d have thought that celebrating the betrothal of the queen’s lady in waiting would call for a fiery display of tomfoolery where the dance floor was limited to flaming torches placed where needed. Talk about setting the stage on fire. This meant that if any of the dancers, His Majesty included, got too close to the flames, well, let’s just say there was going to be enough smoke to encourage buckets of laughter.

This writer would have loved to see the look on the queen’s face when she realized that she couldn’t tell her husband apart from the other similarly dressed courtiers. This writer also thinks that if her royal hubby had caught fire, said queen might have simply stated, ‘That be-eth, not my King, let the fool of a courtier burn.’

What About Italy?

This is technically a ‘contrary belief’, but it wasn’t until much later in the 16th century that the ‘Masquerade Ball’ came to be associated with Italy. It was the Renaissance period, and even this art form seemed to have found ‘rebirth’ as well as re-definition.

Venetian aristocrats took this celebration as a means to enjoy ‘secret desires’ while still retaining their anonymity. A night of scandal and everyone is masked, and we can do whatever we want with whoever we want? Not just Italians, but most anyone in the world would have said yes to the prospect.

The Venetian Carnival celebrations were certainly a blast. They included all sorts of cravings, and we aren’t referring to the food-fest that was also held during such events. Only time could put an end to such decadence, and time certainly did.

The 18th Century came along and saw the curtains close on the Venetian Republic (1797, to be exact). ‘No more parties for you.’ But time turned a blind eye to a certain Swiss Count who resurrected the infamous Masquerade balls.

‘Let the revels begin,’ he might have declared. To which an informed party-goer might have replied, ‘You mean, let the revels continue.’ He’d have doffed his hat at the Count, adjusted his mask, and pursued a certain someone who was last seen heading into the palace gardens.

Merry Old England

John James Heidegger is the name of the Count we mentioned earlier. Whatever costumes remained from the age of Venetian Masquerading, Heidegger took with him to London. The 18th century must have been a curiously fun era, what with public dances being held in gardens all over London, and each event themed to fit the Masquerade-ball concept.

It started off with John James Heidegger holding operatic performances, some of which even impressed the then-reigning King George II. Heidegger then gradually branched out the Masquerade theme and used it as a means to promote haute couture among the English people. It was also during this time when Masquerade masks became the focus of a game, namely one that involved guessing or discovering each other’s identities.

Under Heidegger, the ill-reputed Masquerade party was tailored for a more refined class of party-goers, ones with taste, sophistication, and mystery. In other words, the British. By this time, the Masquerade ball had acquired a distinctly immoral reputation, especially from the stories that came out of colonial America.

Gradually, some of the finest halls in England kept hosting more and more dignified versions of the Masquerade. Instead of raucous music and bugger-all dancing, waltzes and courteous exchanges often graced such occasions.

Are You Going To Get To The Gruesome Part?

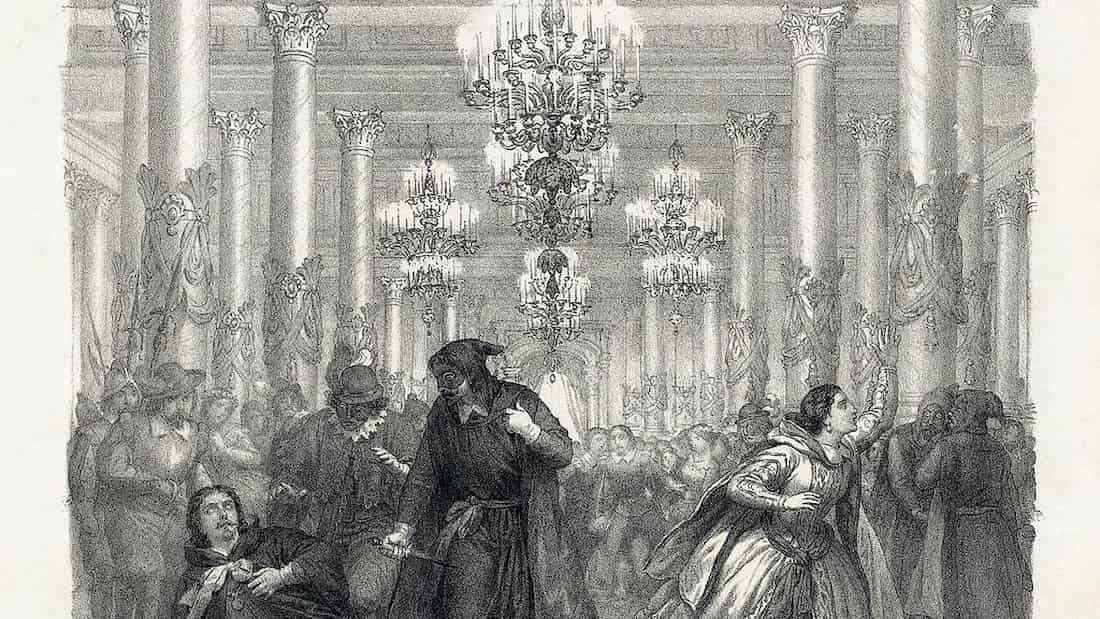

Sweden’s 1771 King, Gustav III, was not a fan of his own parliament. He despised their reforms so much that he stood vocally opposed to nearly everything they wanted. Anyone with half a brain would have guessed that this King wasn’t going to sit quietly for too long. He wanted what amounted to a royal autocracy, and that’s exactly what he devised.

He seized power from his own parliament through a coup d’état, little realizing that despite achieving his dreams Gustav III earned himself some powerful enemies. It so happened that this Swedish King hosted a Masquerade ball where everyone came wearing, um, masks. This included an assassin who slipped into the ball and slipped a certain something into the King that ended his life.

The core definition of ‘risk’ came to suffuse Masquerades ever after, as many a stage-play and operatic performance would testify in the decades to come. Speaking of which, while you’re still in the mood for a Masquerade, go check out the 2004 movie-musical “Phantom of the Opera”. They have an entire number dedicated to this party theme. Three guesses as to what it’s called.

The Modern Masquerade

If you imagined Masquerade party decorations and night club themes, you stand well within the idea of modern-day Masquerade parties. You may be asked to wear something apt, but that’s merely a loose rule. Modern Masquerade party themes are used in seasonal events like Mardis Gras, Halloween, and of course Brazil’s own mega-carnivals. You’ll often find some of the grandest ‘Masquerade balls’ being held in Venice and New Orleans.

There is sometimes a formal dress code requirement, one that comes with an insistence on wearing some sort of mask. This mask should either cover the upper portion of your face or all of it. The core aim of the Masquerade is to hide one’s self or identity from the world, socialize, and then be ready for the ‘grand reveal’ when the clock strikes twelve, or whatever suits the host’s fancy.

Such ‘nights of debauchery’ used to see costumes that ranged from Gothic excellence to hand-made pieces styled with feathers, jester-balls, and frills, even puffy outfits that used lace designs. The latter was called ‘Vandykes’ and was inspired by the clothes worn by famous Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck.

The grand old Masquerade ball has come to be associated not just with aristocracies but also vampires. So don’t be surprised if you’re invited to one such peculiar party where you end up having someone not just breathing down your neck, from behind a mask, but soon biting it. Hopefully, they’ll go gentle on you.

And if you happen to find yourself in an actual vampire Masquerade party, much like that exquisite ballroom scene in the 2004 movie “Van Helsing”, let alone many another cinematic and computer-gaming marvel, to say nothing of Fiction Novels… Not to worry, someone might take it upon themselves to introduce you to all the right diners. Oops, wait, I meant dancers.